Last updated on

Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Blood Clots: What’s the Connection?

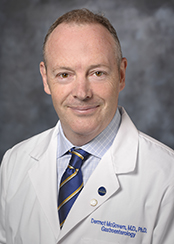

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) affects more than 3 million adults in the U.S., and research shows that patients with IBD have a 3-4 times higher risk of developing thrombosis (blood clots) than people without IBD. Several factors may contribute to this heightened risk, including genetics. We recently spoke to Dr. Dermot McGovern, Director of the Translational Research in IBD and Immunobiology Institute and Director of Precision Health at Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles, CA, to learn more about the link between IBD and blood clots.

Q: Before we dive in, please tell us a little bit about yourself.

I’m a practicing gastroenterologist with an interest in IBD. I also run a lab, where we study how genetics influence the risk of developing IBD and the natural history of the disease – so how it behaves, what complications it can cause, how it responds to therapy, and so on. I oversee the Precision Health Initiative at my institution as well, which combines technology and research to personalize approaches to disease management. In other words, through precision health, we try to match the right treatment to each patient so we can improve outcomes.

Heart Healthy Tip

Donec id elit non mi porta gravida at eget metus. Praesent commodo cursus magna, vel scelerisque nisl consectetur et. Vestibulum id ligula porta felis euismod semper. Donec ullamcorper nulla non metus auctor fringilla. Aenean lacinia bibendum nulla sed consectetur. Praesent commodo cursus magna, vel scelerisque nisl consectetur et.

Q: What is IBD and what does it involve?

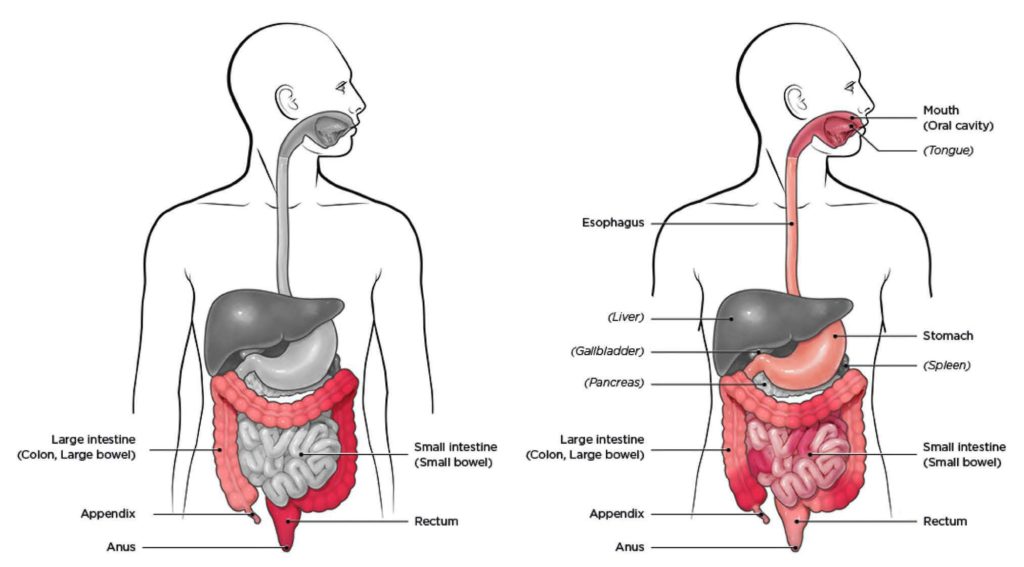

There are two main types of IBD: ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease. Both conditions cause chronic inflammation and damage within the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The GI tract typically helps us digest food, absorb nutrients, and get rid of waste, but the inflammation from IBD interferes with these functions. With Crohn’s disease, the inflammation can affect any part of the gut from the mouth downwards. In UC, the inflammation is limited to the large intestine – the colon.

Historically, IBD was thought to mostly affect people of European ancestry, with the highest risk seen in the Ashkenazi Jewish population (Jews of Eastern European descent). Now we’re seeing more IBD in African American, Hispanic, and Asian populations.

IBD can occur at any age but is most commonly diagnosed before age 35. At that time of life— the teenage years and early adulthood—people experience a lot of personal, social, and professional development, and IBD can be devastating. Symptoms can include stomach pain, diarrhea, rectal bleeding, and fatigue, to name a few – and a lot of our patients have symptoms outside the gut, too. We know that if we don’t control the inflammation and get on top of these symptoms, patients can have a very poor quality of life.

What causes IBD?

We don’t understand the precise causes but do know that IBD occurs in individuals who are at genetic risk and who likely have an abnormal immune response to things in their environment, including their microbiome. The microbiome is a term used to describe the organisms that live in our body and have evolved with us over millions of years. There are trillions of bacteria that live in our gut, along with viruses, fungi, and other things. We normally have a very good relationship with these organisms – they can help keep us healthy. But sometimes things go wrong, and IBD is an example of what can happen when our relationship with our microbiome is compromised.

We’ve made a lot of advances with new treatments, but we’ve still got a lot of work to do. The majority of our patients don’t go into full remission, even with our best treatments. And, unfortunately, a lot of our patients suffer complications – one of which is venous thromboembolism (VTE), also known as blood clots. Blood clots are the #1 cause of death in patients with IBD.

Q: Why does IBD increase the risk of blood clots?

Like most things in medicine, there’s likely more than one factor – but there’s no doubt that inflammation increases the risk. The surface area of the gut is huge by design, because it helps us absorb things as I mentioned. When that area is completely inflamed, the body is faced with a huge inflammatory load, which increases the risk of developing blood clots.

Dehydration may play a role as well. When people are really sick with IBD, they can quickly become dehydrated because they’ve got a lot of fluid loss through diarrhea, etc. They’re probably not as mobile as usual, and many patients often require surgery – surgery in itself is a major risk factor for a blood clot.

Some medications used to treat IBD, such as corticosteroids, may also increase blood clot risk. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) actually put a black box warning on another medication that we use (called a JAK inhibitor) due to a significantly increased risk of VTE – although how significant the actual risk is from these drugs remains controversial.

Q: Is the risk for a blood clot the same across the spectrum of IBD, or is it higher when a person has a flare?

We think the risk is higher when people have a flare, which occurs when the immune system becomes overactive in the gut and causes damage to the lining of the bowel. Patients will notice some distinct IBD symptoms during a flare, like stomach pain, diarrhea, and rectal bleeding. In severe cases—particularly in Crohn’s disease—the bowel can become so narrow that it forms what’s called a stricture. A stricture causes an obstruction, and nothing can go through it. Surgery is often required at that point. So again, remember that both inflammation and surgery are risk factors for VTE, so a flare could certainly put a patient at higher risk of having a clot.

Q: Your research has identified specific genetic traits in patients with IBD that can more than double their risk of developing fatal blood clots. Tell us Your research has identified specific genetic traits in patients with IBD that can more than double their risk of developing fatal blood clots. Tell us more about this study.

This research was spearheaded by a talented scientist in my group, Dr. Takeo Naito. We took two different genetic approaches; first we looked at existing genetic disorders that increase the risk of blood clots, such as factor V Leiden and prothrombin gene mutation. We call these monogenic factors, meaning that you have one single mutation that affects the function of that gene and heightens the risk for blood clotting.

But what’s become increasingly clear from genetics—it’s true in IBD, it’s true in things like breast cancer, and so on—is that the rest of the genome also contributes, but likely in a different way. There are multiple genetic variants across the genome that increase your risk of developing a clot but that individually have a small effect, much smaller than factor V Leiden, for example. If you put all of these small genetic signals together, you can create a “score” of the number of genetic variants that people carry called a polygenic risk score. It’s all just a fancy way of saying that we looked at lots of different genetic variants – more than 250! It’s also important to emphasize that these scores were originally generated in large population groups without IBD.

So, we found that people who had a high polygenic risk score and IBD had a high risk of developing clots. Patients who had both monogenic AND polygenic factors together had an 8-times higher risk of blood clots than people who didn’t have either of those risk factors. In other words, rare genetic changes and more common genetic clotting traits together could greatly impact the risk of blood clots in patients with IBD.

Frequently Asked Questions About Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Blood Clots

I think our study lays an important foundation for more research. My colleagues and I are focused on introducing more personalized approaches to healthcare in general, and understanding both the mono- and polygenic genetic components of risk is a big part of that.

We don’t have the evidence to say that yet – but I hope our study will be a part of that discussion. For now, the most straightforward answer I have is that if you have IBD and develop a blood clot, you should have a conversation with your healthcare provider and decide together if screening would be appropriate.

Other Blood Clot Articles

Optional intro text. Cum sociis natoque penatibus et magnis dis parturient montes, nascetur ridiculus mus. Morbi leo risus, porta ac consectetur ac.

References

Inflammatory bowel disease prevalence (IBD) in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ibd/data-statistics.htm.

Naito T, et al. Prevalence and effect of genetic risk of thromboembolic disease in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:771-780.

What is IBD? Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America. https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/what-is-ibd.

*Originally published in The Beat – April 2021. Read the full newsletter here.